This story originally appeared in the Times of Israel and is reproduced with permission.

From the outside, the house in Ramat Gan, a suburb of Tel Aviv, doesn’t look all that unusual. Only the heavy blue security gate and warning signs at the entrance — only a few blocks from Tel Hashomer Medical Center — hint at what’s inside.

The colorful cartoon characters decorating the lobby add a lighter touch to more the somber, but essential, decor: Anti-bacterial paint on all interior walls; double-glazed windows, with shutters between the window panes to keep out dust and dirt; extra-large tiles, making the floor easier to clean; a custom air-conditioning system that maintains air pressure as well as airflow out of the building; strict hygienic controls for everyone who walks into the place; and protection from the sun in outdoor areas.

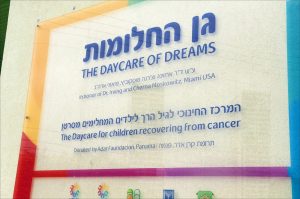

Welcome to Israel’s Daycare of Dreams (or “Gan HaHalomot” in Hebrew) — a purpose-built kindergarten for tots with cancer billed as “the world’s first sterile educational and recovery center.”

Indeed, a quick Google search revealed only one other facility resembling Daycare of Dreams: the Morgan Center in Suffolk County, New York. But while that Long Island kindergarten takes precautions to protect children with suppressed immune systems, it wasn’t built from the ground up specifically with those kids in mind.

Ayelet Rafalin, the director at Daycare of Dreams, said her 4,300-square-foot facility is designed to resemble a hospital isolation ward — without a hospital feel to it.

“The children who come here are sick, but they have permission from their doctors to visit only this place,” said Rafalin, who’s run the facility since its opening in late 2014. “They can be together with other children who also have compromised immune systems. But if they come into contact with sick kids — even though they may have finished their treatment — it could be deadly for them.”

In fact, only a few weeks ago, the kindergarten reopened after a 28-day closure because one child was accidentally exposed to chicken pox.

“We don’t take any chances,” Rafalin said. “Everything had to be scrubbed down, and the kids had to go to hospitals and get treated, since not everyone can receive vaccinations. Without this treatment, they couldn’t come back here.”

Reducing contamination risks

Daycare of Dreams is the flagship project of Larger Than Life, a nonprofit group established in 2000 to assist Israeli children recovering from cancer, regardless of their religion, ethnic background, gender or socioeconomic status. Since then, the organization has helped more than 15,000 children and their families endure the hardships of pediatric cancer.

At the moment, 35 boys and girls from six months to seven years of age attend school here, with the average child staying one to two years. Some come from as far away as Haifa — a two-hour commute — every day.

Most of these kids have lymphomas of various types, while six or seven suffer from leukemia, and another half a dozen have brain tumors. One little girl has uterine cancer, and another small child has diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma (DIPG), a rare, aggressive type of brain tumor that usually results in death within nine months of diagnosis.

“Sometimes the parents know there’s no cure. We have five children like this here now,” said Rafalin. “This is a very happy place. We give them the feeling they’re normal. They can study here, learn to read and write, sit with other children. If they’re tired, they can go to sleep.”

Daycare of Dreams has a 22-member staff, with 14 people on site every day. Like Rafalin, who has degrees in education management and special education, all have previously worked with children with special needs.

“Before coming here, many of these kids were alone with their parents. They don’t have friends their age. It takes a long time until you see them having fun,” Rafalin said, noting that they’re often embarrassed about their baldness as a result of chemotherapy. Others have a hard time walking or keeping food down. “You can meet kids here who haven’t spoken for a year, because they were afraid. And now you have to encourage them to make eye contact and speak again.”

Besides all the architectural considerations, this specially constructed facility also makes sure those who visit wear face masks. Staffers wash their hands often, and every evening, a cleaning crew thoroughly scrubs the tables, chairs, toys and anything else the kids may come in contact with — all this to reduce further the risk of contamination.

Help for kids of all ethnicities

Ellin Yassky is Larger Than Life’s fundraising director.

“When a child leaves here and graduates from kindergarten, he or she is well enough to be integrated into a normative school system, and in their age group. They won’t be so far behind,” she said, noting that kids with cancer generally miss two to three years of schooling due to their illness and treatments. “That takes away a huge amount of stress. They’re going into a new environment, and anything that helps make it a soft landing is better for the child.”

The kindergarten has helped roughly 50 children recover from cancer annually, said Lior Shmueli, Larger Than Life’s CEO. That’s nearly one-tenth of the 600 or so cases of pediatric cancer diagnosed each year.

“In the last 10 years, we have grown to become the largest organization open to all sick children with life-threatening disease,” said Shmueli, adding that his group serves Arabs, Jews, whites, blacks, religious and secular kids — and all others — because cancer doesn’t discriminate.

“The religious organizations in Israel serve only the haredim [ultra-Orthodox Jews],” Shmueli said. “For us, that’s unacceptable.”

Unlike Arizona, U.S.-based Make-A-Wish International, a foundation that fulfills one dream for one child, “Larger Than Life is with families the whole time — from the first day of diagnosis, all the way until the child’s full recovery three or four years later,” Shmueli said. “We support them all the way to the end.”

Rates of survival now average just over 80 percent, depending on the type of cancer. These days, about 90 percent of kids with leukemia make a full recovery, with much lower recovery rates for those with brain tumors or Hodgkin’s lymphoma.

“The statistics in Israel are the same as in the Western world,” Shmueli said. “Today, Israeli children receive the same medical protocols as a child in Europe or the [United] States.”

Summer camps and smile trains

Claude Grundman-Brightman, an official of Netanya Academic College who chairs Israel’s Friends of Larger Than Life, said: “Our medical team as well as psychologists and other staffers take a total approach to do whatever is necessary to lighten the pressure and stress on families. This is rare, because organizations usually do just one thing rather than take a total approach.”

As such, the organization arranges for 300 sick kids and their siblings to attend summer camps around Israel. It pays transportation costs to hospitals for families that have no car or way to get there, and at the midpoint of a child’s chemotherapy, it takes the entire family for a week-long “recovery vacation” to Eilat for some time off, and sponsors the Purim Carnival Smile Train.

Twice a year, Larger Than Life also flies 40 kids across the ocean for a U.S. vacation — usually in October to Los Angeles and in March to Orlando, home of Disney World.

In June 2018, Larger Than Life organized Israel’s first conference on treatments and clinical trials for kids with cancer. The event, led by Miriam Ben Harush, director of the hematology-oncology department at Haifa’s Rambam Hospital, included 70 physicians, specialists, nurses and researchers from across Israel.

Building on the success of its Tel Aviv-area facility, Larger Than Life has already begun construction of a second, even larger sterile kindergarten in the southern Israeli city of Beersheva to serve the entire Negev Desert. Many of the Jewish, Arab and Bedouin kids with cancer in Israel’s southern periphery come from poor families, and their parents can’t afford to care for their sick child.

For this reason, the Beersheva project — estimated to cost $3 million — envisions an extended educational center that will serve kids from 7 to 11 years of age, as well as preschool and kindergarten-age children. Located adjacent to Soroka Medical Center, it will include four classrooms for grades 1 through 4, as well as a kindergarten classroom outfitted with a toddlers’ nursery and Gymboree play area.

A network of kindergartens

Larger Than Life has started work on its third and fourth centers — in Haifa and Jerusalem — and eventually hopes to have a network of eight sterile rehabilitation and recovery centers next to every Israeli hospital that has a pedriatic cancer ward.

All this costs money, of course. The Beersheva facility alone is estimated to cost $3 million.

Larger Than Life operates on an annual budget of 25 million shekels, or about $7 million. Less than half of one percent of that comes from government funds. The rest are all donations — 65 percent from within Israel, 25 percent from overseas, and the remaining 10 percent in in-kind goods and services.

To meet its goals, the charity aims to raise $12 million during 2019. On Feb. 10, it will sponsor an annual gala fundraising concert in Tel Aviv’s largest concert hall featuring Rami Kleinstein, Shiri Maimon and other popular Israeli musicians; some 2,400 people are expected to attend. Its New York-based affiliate, Larger Than Life USA, is registered as a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization.

Besides the kindergartens and summer camps, the charity spends about $1 million a year on cancer medications not reimbursed by Israel’s Ministry of Health. It also brings about 100 Israeli kids a year to receive specialized treatment in North America — mainly at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) in Bethesda, Maryland; Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York; Toronto’s Hospital for Sick Children, and the Laurie Proton Therapy Center at New Jersey’s Rutgers Cancer Institute.

For families lacking private insurance, Larger Than Life pays for an apartment rental, a car, round-trip airfare and other expenses to allow the immediate family of a sick child to travel there as well; the average expenditure comes to $10,000 per patient.

“We are not doctors. Rather, we give the doctors support so they can do everything they need to save the child,” Shmueli said. “And if a doctor says the only suitable treatment for a kid is at NIH, for example, sometimes we’ll spend up to a million shekels. It might be a new type of research that can be done by a pharmaceutical company only in a certain hospital somewhere.”

He added: “Even if it’s only 20 children a year, for us every child is 100 percent.”