People infected with the Epstein-Barr virus have a higher chance of developing Hodgkin’s lymphoma, according to a new study, because a viral protein called BNRF1 leads to a faulty division of chromosomes when B-cells divide, increasing their risk of becoming cancer cells.

The study, “Epstein-Barr virus particles induce centrosome amplification and chromosomal instability,” appeared in Nature Communications.

Most of the world’s inhabitants carry the Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), a member of the herpes family known to cause infectious mononucleosis, or the kissing disease. Although the virus has no clinical consequences for most infected people, it is associated with up to 2 percent of all cancers. But EBV’s precise role in turning infected cells into cancer cells remains unclear.

“The contribution of the viral infection to cancer development in patients with a weakened immune system is well understood,” Henri-Jacques Delecluse, a cancer researcher at the German Cancer Research Center (Deutsches Krebsforschungszentrum, DKFZ) in Heidelberg, said in a press release. “But in the majority of cases, it remains unclear how an EBV infection leads to cancer development.”

Attempting to unravel this mechanism, researchers infected B-cells with EBV and studied them in culture and in mice models.

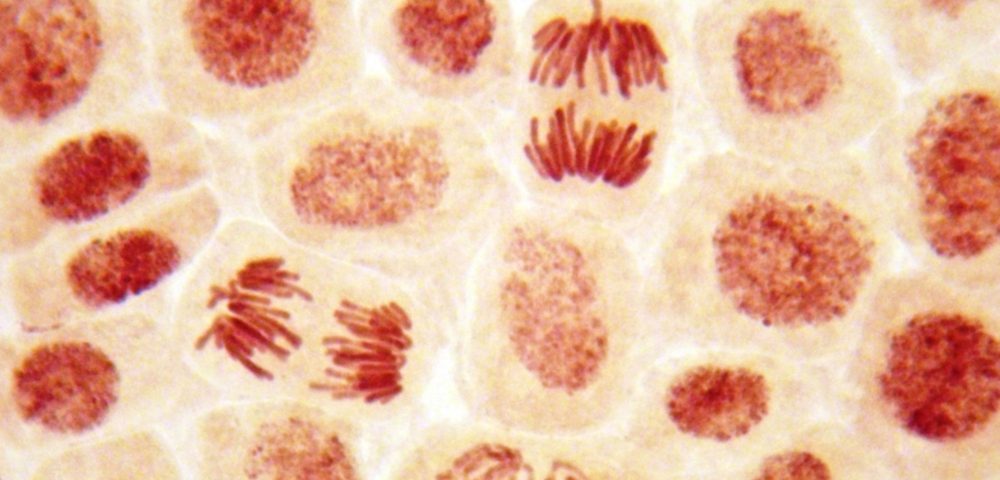

When a cell normally divides, two spindle poles, or centrosomes, push the chromosomes in opposite directions, dividing chromosomes equally and accurately between two daughter cells. But when EBV comes in contact with a dividing cell, BNRF1 — a viral protein found in the infectious particle — causes too many centrosomes to form. This leads to the inaccurate division of chromosomes, a known risk factor for cancer.

Consistently, when the researchers used EBV deficient in BNRF1, the virus no longer interfered with chromosome division between daughter cells.

“The novelty of our work is that we have uncovered a component of the viral particle as a cancer driver,” Delecluse said. “All human tumor viruses that have been studied so far cause cancer in a completely different manner. Usually, the genetic material of the viruses needs to be permanently present in the infected cell, thus causing the activation of one or several viral genes that cause cancer development. However, these gene products are not present in the infectious particle itself.”

The identification of this novel mechanism has led Delecluse and colleagues to suspect that EBV could be causing more cancers than previously thought. Such cancers might have not been linked with the virus because they did not contain viral genetic material.

“We must push forward with the development of a vaccine against EBV infection. This would be the most direct strategy to prevent an infection with the virus,” said Delecluse. “Our latest results show that the first infection could already be a cancer risk and this fits with earlier work that showed an increase in the incidence of Hodgkin’s lymphoma in people who underwent an episode of infectious mononucleosis.”