Wistar Institute researchers recently discovered that a protein in the endoplasmic reticulum, called STING, can stimulate the immune system to kill malignant B-cells — the cause of several lymphomas.

The study, “Agonist-Mediated Activation of STING Induces Apoptosis in Malignant B Cells,” was published in the journal Cancer Research.

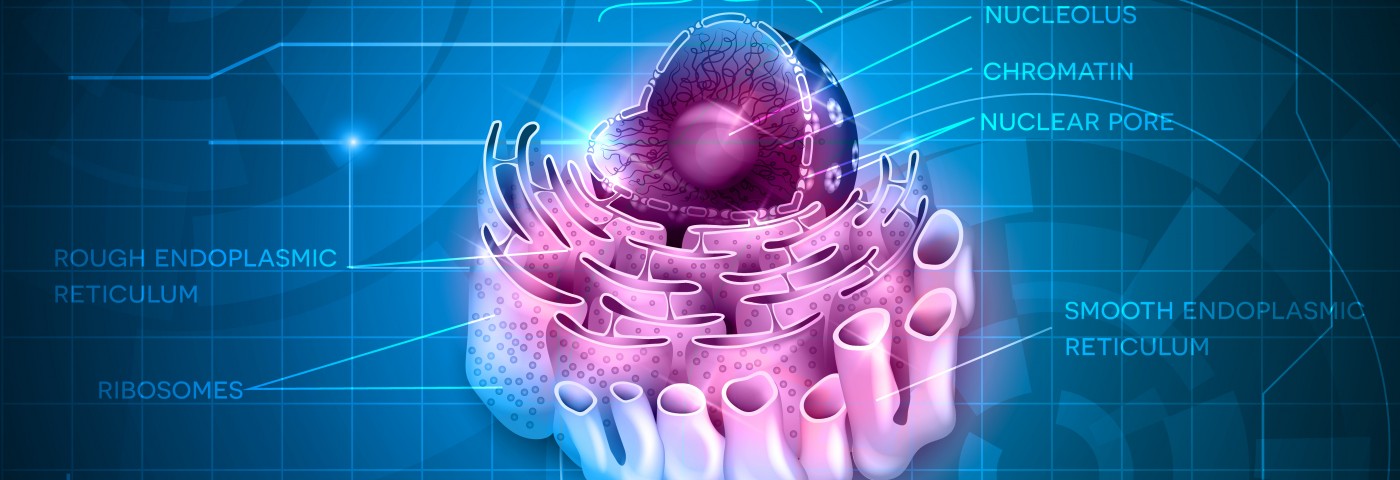

The endoplasmic reticulum is a network of membranes sprouting from the cell nucleus, and a hub for metabolism control and protein production. Researchers have been searching for potential drug targets within these membranes for some time.

STING is involved in producing type 1 interferons — immune mediators that help to regulate the immune system. Drugs targeting the protein have been shown to trigger immune responses, and were developed to increase the efficiency of cancer treatment. These so-called STING agonists have been used both as cancer immunotherapy and as an adjuvant in vaccines.

Researchers first believed that the agonists only worked by boosting the response of the main anticancer drug or vaccine, but later research showed that the drugs induced programmed cell death in both normal and malignant B-cells. This would allow the use of STING stimulators as the primary therapy for B-cell related cancers, such as leukemia, lymphoma, and multiple myeloma, but stimulating the protein has produced only transient results to date.

“In non-B cells, STING agonists stimulate the production of interferons, but since they induce apoptosis in B cells, these B-cells do not live long enough to help boost the immune response,” Chih-Chi Andrew Hu, associate professor at The Wistar Institute and senior author of the study, said in a press release. “We wanted to determine why STING agonists behave differently in normal and malignant B cells and how to extend this cytotoxic activity in malignant B-cell leukemia, lymphoma, and multiple myeloma.”

The research team focused on a pathway associated with STING function: the IRE-1/XBP-1 stress response pathway. If cells lack either IRE-1 or XBP-1, stimulation of STING does not lead to the production of interferons. B–cell-related cancers are also dependent on the pathway for survival. The researchers noted that when the pathway was activated, the number of dying cells was reduced.

When the team stimulated STING, the IRE-1/XBP-1 pathway was suppressed, which increased the level of programmed cell death in malignant B-cells in culture. The team could also confirm the results in mouse models of chronic lymphocytic leukemia and multiple myeloma, where the treatment induced cancer regression.

“This specific cytotoxicity toward B cells strongly supports the use of STING agonists in the treatment of B-cell hematologic malignancies,” said Chih-Hang Anthony Tang, the study’s first author. “We also believe that cytotoxicity in normal B-cells can be managed with the administration of intravenous immunoglobulin that can help maintain normal levels of antibodies while treatment is being administered. This is something we plan on studying further.”