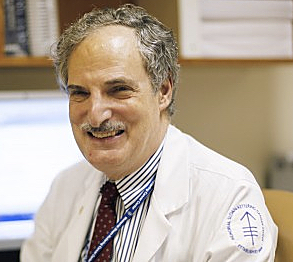

Dr. David Straus, a medical oncologist who specializes in treating blood cancers, including lymphoma, at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC) in New York City, is focused on finding Hodgkin lymphoma treatment regimens that result in fewer side effects without compromising their success rates.

His work was prompted by studies showing that, while most HL patients live long and healthy lives, a significant number can suffer complications decades later from treatments like radiation and chemotherapy, including secondary cancers and heart problems.

Lymphoma, the most common category of blood cancer, has two main variants: Hodgkin lymphoma (HL) and non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL). There are six types of Hodgkin lymphoma, and some 15 percent of diagnosed lymphoma cases are HL according to the American Cancer Society.

Chemotherapy, radiation therapy, or a combination of the two are typically used to treat Hodgkin lymphoma, which often is diagnosed in young adults, making advances in reducing a treatment’s long-term side effects especially important. Bone marrow or stem cell transplantation may also be an option under special circumstances.

In an article published Jan. 20 on the MSKCC website, medical and science writer Julie Grisham reports that Dr. Straus has conducted a study investigating how patients with early stage disease respond to less-intense treatment, noting that early results indicate these patients do well without radiation therapy and with less aggressive chemotherapy. Dr. Straus cautions, though, that more time is needed to confirm these initial findings.

In December, Dr. Straus presented his findings at the American Society of Hematology (ASH) annual meeting at San Diego, California. The Phase 2 multicenter study used PET scans to monitor the presence of residual disease after initial treatment to help determine whether additional treatment would be appropriate.

Dr. Straus is an attending physician in the Lymphoma Service at the MSKCC Department of Medicine, and has had a large clinical practice for more than 30 years, primarily treating patients with malignant lymphomas, chronic lymphocytic leukemia, and multiple myeloma.

His website notes his longstanding research interest in malignant lymphomas, and reports that he has authored more than 150 publications on the topic, and served as a reviewer for publications in the field and for grant applications to the National Institutes of Health. He has conducted clinical trials in Hodgkin lymphoma, cutaneous T-cell lymphomas, and HIV-associated lymphomas, and studies assessing quality of life and survivorship issues among lymphoma patients.

A central focus of Dr. Straus’ research is documenting and attempting to improve the outcome of long-term Hodgkin lymphoma survivors. Dr. Straus tells Grisham that the average age of patients in the most recent study was between 25 and 30, which is typical for people with Hodgkin lymphoma. He notes that while patients cured through standard treatment regimens should expect to live a long time, studies also show that 40 years after treatment, only 25 percent of Hodgkin lymphoma survivors are still alive, with most premature deaths related to late-manifesting complications of treatments, particularly those involving radiation therapy. Dr. Straus observes that the leading cause of death among Hodgkin lymphoma survivors are secondary cancers, which are usually related to radiation therapy, with an additional complication of residual chemotherapy side effects in some cases.

Radiation therapy to the neck and chest area also can lead to cardiovascular damage, a narrowing of arteries in the neck that can cause strokes, coronary artery disease, and heart valve scarring — with the risks amplified when both radiation and chemotherapy are used.

ABVD is a chemotherapy regimen used in first-line treatment of Hodgkin lymphoma, containing A: doxorubicin (Adriamycin), B: bleomycin (Blenoxane), V: vinblastine (Velban) and D: dacarbazine (DTIC-Dome). In his ASH presentation, Dr. Straus reported that his Phase 2 trial, using PET scans as a biomarker to tailor treatment, found disease relapse in only eight of 131 patients who had received a less-intensive ABVD-only treatment after an average follow-up of two years. That rate, he reported, was as good as or better than what would be expected in patients receiving more prolonged chemotherapy and radiation treatment. Further, he expected that patients with PET-negative disease — no cancer detectable on the scan — have a very low likelihood of their disease coming back.

Dr. Straus cautions that these are early results, and that team will continue follow-up with these patients. But in the meantime, these preliminary indications suggest a less-intensive treatment approach may be equally beneficial to patients with fewer long-term side effects.

With patients who need radiation therapy, Dr. Straus and colleagues are investigating ways it might be done more safely, and are planning a study with MSKCC radiation oncologist Oren Cahlon on substantially decreasing the size of tissue areas treated with standard radiation therapy, and on using newer, more precise techniques such as proton beam therapy to reduce exposure to other organs and tissues.

With patients who need radiation therapy, Dr. Straus and colleagues are investigating ways it might be done more safely, and are planning a study with MSKCC radiation oncologist Oren Cahlon on substantially decreasing the size of tissue areas treated with standard radiation therapy, and on using newer, more precise techniques such as proton beam therapy to reduce exposure to other organs and tissues.

Dr. Cahlon notes that at Memorial Sloan Kettering, he and other radiation oncologists use modern radiation techniques that include prone treatment, deep inspiratory breath hold, partial breast irradiation, intensity modulated radiation therapy (IMRT) and proton therapy. Proton therapy delivers high doses of radiation to radio-resistant tumors to improve long-term disease control while minimizing the amount of radiation delivered to healthy tissues located in close proximity to tumors.

Currently, proton therapy technology is available at 12 centers in the United States. Dr. Cahlon and other Sloan Kettering radiation oncologists also treat select patients with proton beam therapy at the ProCure Proton Therapy Center in Somerset, New Jersey — the only proton facility in the New York-New Jersey-Connecticut tri-state region that offers pencil beam scanning (PBS), an ultra-narrow proton beam that deposits radiation doses even more precisely within a tumor. PBS enables doctors to precisely “paint” the tumor with radiation, further minimizing radiation exposure to healthy tissues and reducing the risk of side effects.

Dr. Cahlon, the director of Proton Therapy at Memorial Sloan Kettering, is participating in several clinical trials to better characterize the potential benefits of proton therapy as well as to optimize its delivery.

Dr. Straus has a particular reason for his research focus. As he told Grisham: “It’s sad for me when these patients whose cancer I have treated come back to see me years later and they’re suffering from all these side effects. It is also very frustrating to have cured the Hodgkin lymphoma only to have them die of the complications of treatment. And although the radiation therapy that’s given today is safer than what was used when many of these now middle-aged patients were treated, we think that it could be administered even more safely if it is necessary.”

Dr. Straus’ study was sponsored by the Alliance for Clinical Trials in Oncology, the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group, and the Southwest Oncology Group, and was supported in part by the National Cancer Institute under grants U10CA180821, U10CA180820, and U10CA180888.

Sources:

Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC)

American Cancer Society