In a study entitled “Targeting Human Cancer by a Glycosaminoglycan Binding Malaria Protein” researchers report that, while attempting to find a malaria vaccine that fights the disease in pregnant women, they found what could actually become an effective strategy against cancer. The study was published in the journal Cancer Cell.

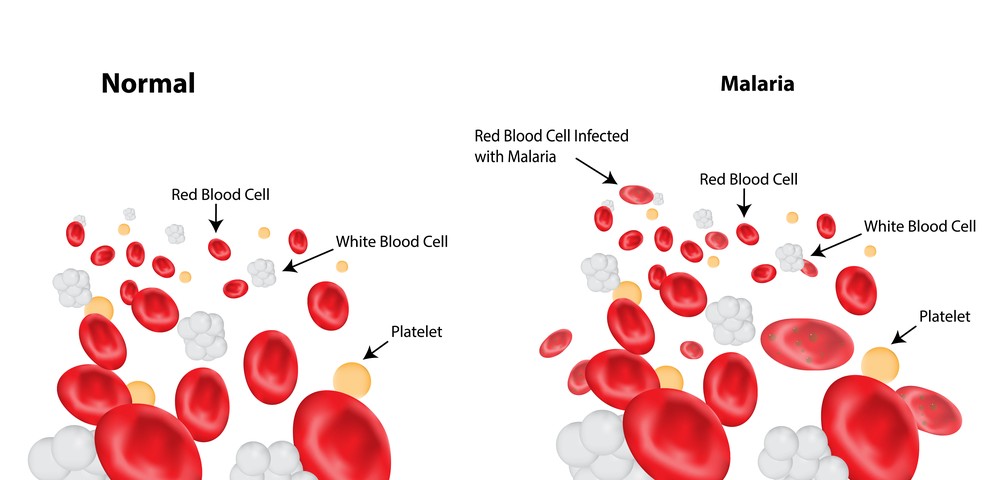

The malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum, once inside erythrocytes, is responsible for these cells’ expression of a malaria protein called VAR2CSA, which allows the infected erythrocytes to bind specifically in the placenta of pregnant women. This interaction is mediated by a placenta-specific chondroitin sulfate (CS) modification. Notably, researchers now discovered that this CS modification is also significantly present in cancer cells, meaning that a potential malaria vaccine targeting VAR2CSA may also work in tumor cells.

In this study, researchers at the University of Copenhagen and the University of British Columbia designed a malaria VAR2CSA protein and attached it to a toxin. They found that when given to cancer cells, and even to mouse models of cancer, the combination of the malaria protein and toxin was absorbed by cancer cells and, once inside, released the toxin, killing malignant cells.

Ali Salanti, from the Department of Immunology and Microbiology at the University of Copenhagen and the study first author, noted, “For decades, scientists have been searching for similarities between the growth of a placenta and a tumor. The placenta is an organ, which within a few months grows from only few cells into an organ weighing approx. two pounds, and it provides the embryo with oxygen and nourishment in a relatively foreign environment. In a manner of speaking, tumors do much the same, they grow aggressively in a relatively foreign environment. We examined the carbohydrate’s function. In the placenta, it helps ensure fast growth. Our experiments showed that it was the same in cancer tumors. We combined the malaria parasite with cancer cells and the parasite reacted to the cancer cells as if they were a placenta and attached itself.”

Both teams of researchers tested samples from different cancers (brain tumors to leukemias) and discovered that 90% of all cancer cells are permissive to the binding of the malaria protein. They tested the malaria protein-associated toxin on mice implanted with three cancer models – non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, prostate cancer, and metastatic bone cancer – and all tested cancers responded to the toxin-mediated therapy. Particularly, in non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, researchers observed significant tumor shrinkage (about a quarter of their size) when compared to controls.

Thomas Mandel Clausen, a PhD student and co-first author in the study, added, “It appears that the malaria protein attaches itself to the tumor without any significant attachment to other tissue. And the mice that were given doses of protein and toxin showed far higher survival rates than the untreated mice. We have seen that three doses can arrest growth in a tumor and even make it shrink.”

The treatment, however, cannot be applied to pregnant women since, as Salanti explained, “Expressed in popular terms, the toxin will believe that the placenta is a tumor and kill it, in exactly the same way it will believe that a tumor is a placenta.”

The discovery prompted the creation of a biotech company, the VAR2pharmaceuticals, by the University of Copenhagen in collaboration with the scientists to now investigate the potential therapeutic effects of their discovery in clinical trials. Noted Salanti, “The earliest possible test scenario is in four years time. The biggest questions are whether it’ll work in the human body, and if the human body can tolerate the doses needed without developing side effects. But we’re optimistic because the protein appears to only attach itself to a carbohydrate that is only found in the placenta and in cancer tumors in humans.”