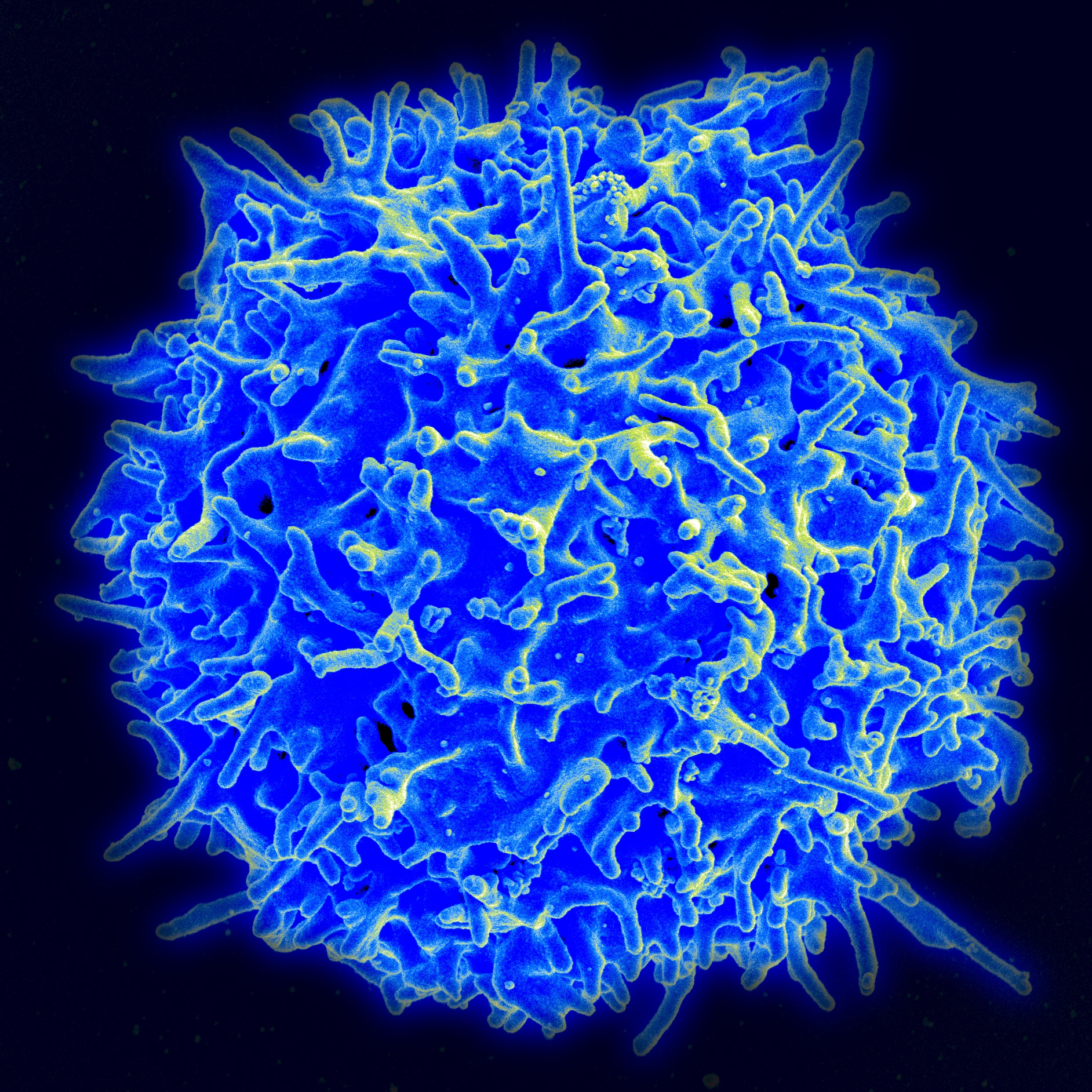

A new study from researchers at the Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia indicates that a DNA cutting mechanism may sometimes misfunction, leading normal immune cells known as T and B cells (lymphocytes, also called white blood cells) to turn into blood cancers. By understanding these DNA “editing errors” scientists may be able to develop new blood cancer treatments. The research, titled “Off-Target V(D)J Recombination Drives Lymphomagenesis and Is Escalated by Loss of the Rag2 C Terminus“ appeared September 10, 2015, in the online journal Cell Reports.

According to the Leukemia Research Foundation “Every four minutes, someone is diagnosed with blood cancer – more than 201,870 new cases are expected this year in the United States.” New treatments for blood cancers, such as lymphoma–both Hodgkins and non-Hodgkins–are greatly needed.

Matina Mijušković of the Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine led the study. To look at whether DNA editing may go awry in blood cancers, the scientists used mouse models of cancer. They were specifically interested in V(D)J recombination errors, a type of genetic rearrangement that happens when T and B cells are developing.

Researchers analyzed tumors known as “thymic lymphomas” that were taken from genetically altered mice that completely lacked a gene known as Tp53. The protein that this gene codes for suppresses tumor growth, so mice without it grow tumors. They also studied mice with a mutation of the Rag2 gene, created at region 352 of the gene. Rag stands for “recombination activating gene.” The protein that this gene codes for is involved in T and B cell development and mutations at region 352 of its DNA cause a rapid onset of cancer.

The investigators found DNA editing errors in 275 different regions. Overall, when the Rag2 protein is altered in a region known as the C terminus, the errors are more likely to occur. Changes in Rag2 may be specifically responsible for blood cancers. In their report they conclude “The systematic analysis revealed numerous off-target, RAG-mediated rearrangements in known and suspected cancer genes, which were escalated by the loss of Rag2 C terminus.”

Understanding these editing errors and targeting them with specific medications may ultimately aid in the treatment of blood cancers such as lymphoma or leukemia. Therapies that specifically act on Rag2 and that prevent the loss of the Rag2 C terminus may be particularly useful in the future for treating individuals with these malignancies.